An experiment is a procedure that yields one of a given set of possible outcomes. The sample space of the experiment is the set of possible outcomes. An event is a subset of the sample space.

DEFINITION

If S is a finite nonempty sample space of equally likely outcomes, and E is an event, that is, a subset of S, then the probability of E is p(E) = |E| / |S|

Let E be an event in a sample space S. The probability of the event E = S − E, the complementary event to E, is given by p(E) = 1 − p(E).

What is the probability that when

two dice are rolled, the sum of

the numbers on the two dice is 7?

There are a total of 36 equally

likely possible outcomes when two

dice are rolled.There are six successful

outcomes, namely,

(1, 6), (2, 5), (3, 4),

(4, 3), (5, 2), and (6, 1),

where the values of the first

and second dice are represented

by an ordered pair.

Hence, the probability that

a seven comes

up when two

fair dice are rolled is 6/36 = 1/6.

Find the probability that a hand of five cards in poker contains four cards of one kind

By the product rule, the number of hands of five cards with four cards of one kind is the product of the number of ways to pick one kind, the number of ways to pick the four of this kind out of the four in the deck of this kind,and the number of ways to pick the fifth card.This is C(13, 1) C(4, 4) C(48, 1).By Example 11 in Section 6.3 there are C(52, 5) different hands of five cards. Hence, the probability that a hand contains four cards of one kind is (C(13, 1) C(4, 4) C(48, 1))/ C(52, 5) = (13 · 1 · 48) / 2,598,960 ≈ 0.00024.

Let E1 and E2 be events in the sample space S. Then p(E1 ∪ E2) = p(E1) + p(E2) − p(E1 ∩ E2).

What is the probability that a positive integer

selected at random from the set of positive integers

not exceeding 100 is divisible by either 2 or

5?

Let E1 be the event that the integer

selected at random is divisible by 2, and let

E2 be the event

that

it is divisible by

5.

Then E1 ∪ E2 is the event that it is divisible by either 2 or 5.

Also, E1 ∩ E2 is the event

that it is divisible by both 2 and 5,

or

equivalently, that it is divisible by 10.

Because |E1| = 50, |E2| = 20, and |E1 ∩ E2| = 10, it follows that p(E1 ∪ E2) = p(E1) + p(E2) − p(E1 ∩ E2)= 50/100 + 20/100 - 10/100 = 3/5.

Probabilistic reasoning is using logic and probability to handle uncertain situations.

An example of probabilistic reasoning is using past situations and statistics to predict an outcome.

It is used to define which of two events is more likely.Analyzing the probabilities of such events can be tricky. The below example describes a problem of this type.

We defined probability of an Event E as the number of outcomes in E divided by total number of outcomes.This definition assumes that outcomes are equally likely.

However, many experiments have outcomes that are not equally likely. For instance, a coin may be biased so that it comes up heads twice as often as tails.

In this section we will study how to define probabilities where outcomes are not equally likely.

Let S be the sample space of an experiment with a finite or countable number of outcomes. We assign a probability p(s) to each outcome s.

We require that two conditions be met:

The function p from the set of all outcomes of the sample space S is called a probability distribution.

The probability p(s) assigned to an outcome s should equal the limit of the number of times s occurs divided by the number of times the experiment is performed, as this number grows without bound.

DEFINITION 1

Consider a set S with n elements, then, the probability of each element of S considering uniform distribution is 1/n.

Complements:

p(E)

= 1 - p(E)

THEOREM 1

The probability of any event composed of a sequence of disjoint events is just the sum of the individual probabilities.

THEOREM 2

If E and F are events in the

sample space S, then:

p(E ∪ F)

= p(E) + p(F)

− p(E ∩ F)

DEFINITION 3

The conditional probability of event E given event F has occurred is defined as:

Let's analyze with our shark example:

E = "bitten by shark" (imagine it's .0005)

F = "shark present" (imagine it's .001)

And E ∩ F = .0005

Therefore, p(E | F) = .5

Or, "Half the time, if there is a shark around, it

bites someone."

DEFINITION 4

Events E and F are independent if and only if p(E ∩ F) = p(E)p(F)

Notice how this was not the case with the shark attacks! Given a shark is around, the probability of a shark bite is much higher than p(E)p(F) (which was .0000005). This would not be true if F were, say, "UFO present."

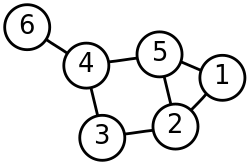

Pairwise independence versus mutual independence:

The best way to understand this difference is to

consider a situation like this, with two coin tosses:

Event A is both tosses are the same.

Event B is the first toss is heads.

Event C is the second toss is heads.

Notice that if B and C both occur, or

both don't occur, A occured for sure.

And if only one of B and C occured,

A didn't occur for sure.

Nevertheless, any two pairs of these events, taken on

their own, are independent.

Bernoulli trial: an experiment with only two

possible outcomes. (The patient lives, or the patient

dies.)

p + q = 1

Many problems can be solved by determining the probability of k successes when an experiment consists of n mutually independent Bernoulli trials. (Bernoulli trials are mutually independent if the conditional probability of success on any given trial is p, given any information whatsoever about the outcomes of the other trials.)

THEOREM 2

The probability of exactly k successes in n independent Bernoulli trials, with probability of success p and probability of failure q = 1 − p, is C(n, k)pkqn−k

Example: Suppose that the probability that a 0

bit is generated is 0.9, that the probability that a 1

bit is generated is 0.1, and that bits are generated

independently. What is the probability that exactly

eight 0 bits are generated when 10 bits are generated?

Answer:

C(10, 8)(0.9)8(0.1)2

= 0.1937102445

DEFINITION 6

A random variable is a function from

the sample space of an experiment to the set

of real numbers. A random variable assigns a

real number to each possible outcome.

Example: Let X(t) be the

number of heads that appear in three coin tosses.

Then, X(HHH) = 3, X(HHT) = 2,

and so on.

DEFINITION 7

The distribution of a random variable is the

complete set of probabilities for each possible

value of the variable.

Example: In the above case of three coin tosses,

P(X = 3) = 1/8, P(X = 2) =

3/8, and so on.

We will study how to use random variables in

section 7.4.

How many people have to enter a party before it is

likely (p > .5) that two of them have the same

birthday?

Note that this resembles a pigeonhole problem,

but with an important difference: we are not asking how

many do we need to be certain two have the same

birthday (answer: 367), but how many do we need for it

to be likely?

We are going to solve this by solving the complement of the problem: we will solve for pn, the probability that they all have different birthdays, and then the probability two will have the same birthday will be 1 − pn. The first person obviously will not have "the same" birthday as anyone else. The probability the second person will have a different birthday is 365 / 366. For the third (assuming no match yet!) it is 364 / 366. And so on.

So our question becomes, at what point does

1 − pn become greater

than .5? And the answer is the surprisingly small

number 23!

All of this would be just a curiosity, except it

is the same question as "How likely is it our

hashing function will produce a collision after

hashing n items?"

In hashing, we are mapping n keys to

m slots, where n is usually

much greater than m. (For instance, possible

student names to 100 slots in a class roster.)

We want to know if students are randomly mapped

to a slot with probability 1/m, how likely

is it that two students will map to the same slot?

(Too many collisions slow down our hashing algorithm.)

These are examples of probabilistic algorithms. Most of the time, we study algorithms that produce a definite answer. But probabilistic algorithms produce correct answers only with some likelihood. A Monte Carlo Algorithm runs repeated trials of some process until the answer it gives is "close enough" to certainty for the purposes of the person or persons employing the algorithm.

Example: For an integer that is not prime, it will pass Miller's test for fewer than n/4 bases b with 1 < b < n. We can generate a large number and try, say, k iterations of the algorithm, and if it passes each iteration, the that it is not prime are (1/4)k. For 30 iterations, this will give us a probability that n is composite of less than 1/1018.

THEOREM 3

THEOREM 4

DEFINITION 1

The expected value of the random variable X

on the sample space S, is

E(X) = Σp(s)

X(s)

This is also called the mean of the random

variable.

Example: The expected value of 1 toss of

a fair die is 7/2.

THEOREM 1

We can also get the above by summing up the

probability-weighted values for X being

equal to each outcome.

Example:

Use two coin tosses to illustrate this.

THEOREM 2

The expected number of successes in n

Bernoulli trials where the probability of

success in each trial is p =

np.

Example:

The expected number of sixes in 36 dice rolls

(where six is success and all other results failure)

is six. (1/6 * 36)

THEOREM 3

EΣ(X1 + X2 + ... + Xn = Σ( E(X1) + E(X2) + ... + E(Xn))

Expected value in the hatcheck problem: The hatcheck employee loses all tickets and gives the hats back randomly. What is the expected number of people who get back the correct hat?

Average case computational complexity of an algorithm is amount of computational resourse used by algorithm,averaged over all possible inputs.It can also be interpreted as computing the expected value of a random variable.

Let us consider aj, j=1,2,....k to be all the outcomes of an experiment and X be a random variable,that defines number of operations used by the algorithm,when aj is an input

Let x1,x2...xk be the respective random variables pj is the probability to each possible input .Then the average case complexity of the algorithm is

Geometric distribution defines random variables with infinitely many outcomes

DEFINITION 2

A random variable X has a geometric distribution with parameter p if p(X = k) = (1 − p)k−1 p for k = 1, 2, 3, . . ., where p is a real number with 0 ≤p ≤ 1.

THEOREM 4

If the random variable X has the geometric distribution with parameter p, then E(X) = 1/p.

Two random variables X and Y are independent if: p(X = r1 and Y = r2) = p(X = r1) * p(Y = r2)

The variance of a random variable defines how widely a random variable is distributed

DEFINITION 4

Let X be a random variable on a sample space S. The variance of X, denoted by V(X), is V(X) =∑ s∈S (X(s) − E(X))2 p(s).

That is, V (X) is the weighted average of the square of the deviation of X. The standard deviation of X, denoted σ(X), is defined to be

√ V(X)

THEOREM 6

If X is a random variable on a sample space S, then V(X)= E(X2) − E(X)2.

COROLLARY 1

If X is a random variable, V(X) = E((X − μ)2)

THEOREM 7

BIENAYMÉ’S FORMULA If X and Y are two independent random variables on a sample space S, then V (X + Y) = V (X) + V (Y). Furthermore, if Xi, i = 1, 2, . . . , n, with n a positive integer, are pairwise independent random variables on S, then V (X1 + X2 +· · ·+Xn) = V (X1) + V (X2)+· · ·+V (Xn).

It defines the likeliness of a random variable to take a value far from it's expected value

THEOREM 8

Let X be a random variable on a sample space S with probability function p. If r is a positive real number, then p(|X(s) − E(X)| ≥ r) ≤ V (X)/r2.