Heliocentrism

I wish to suggest that the history of the Copernican Revolution falsifies Karl Popper's theory of falsificationism. The basic idea of Popper's doctrine is that no amount of positive evidence can confirm a universal theory, but a single negative piece of evidence refutes it. (Both Kuhn and Feyerabend noted this well before me, by the way!)

The main problem with his theory is that this is not how science works. The first point to address is whether that is a valid criticism of a philosophical theory. It could be said that the actual practice of scientists may be flawed, and it is the role of philosophy to mend the error of their ways. But such a view relies on a misunderstanding of what philosophy can and can't do. As noted by Oakeshott in On Human Conduct, a key error of Plato's was to believe that because the philosopher's "platform of understanding" might be superior to the platform of someone who hasn't ascended fully out of the cave; such as the practical man, the historian, or the natural scientist -- that therefore it was a substitute for them. But the philosopher is no more in a position to inform a scientist of how he really should be working, simply because he has examined the scientist's own postulates, than he is to instruct Michael Jordan on how he really should play basketball because he has conducted a philosophical study of the game. As Franco puts it, 'The postulates in which a theorist understands the identities of a conditional platform of understanding are not principles from which correct performances may be deduced. To use theoretical knowledge in this way to direct practical activity is the spurious engagement of the theoretician.'"

The philosopher's true role is to make more clear what the scientist is doing -- as Collingwood put it, he does not seek to rationalize human activities, but to find the rationality that is already in them and clarify its presence.

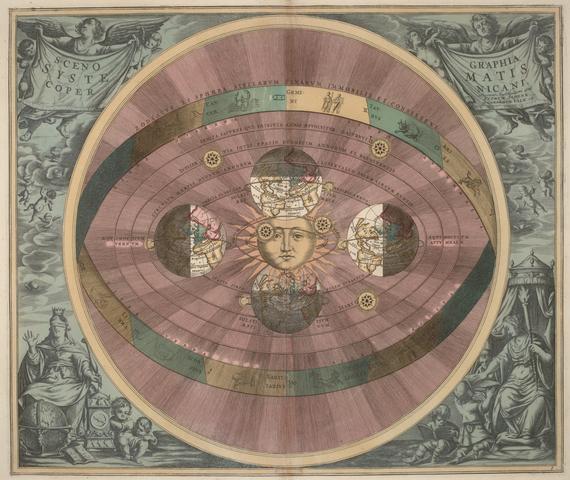

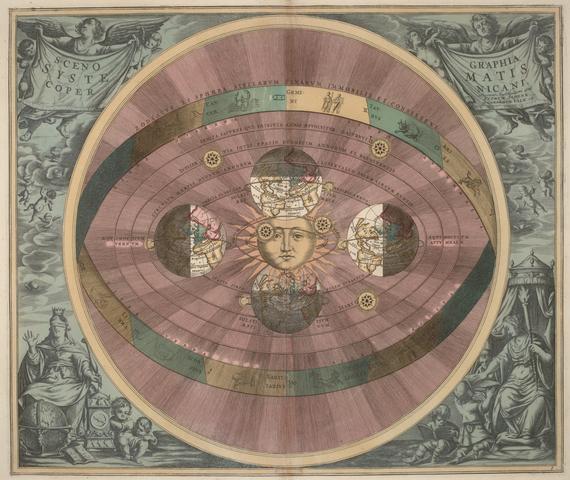

Furthermore, if a philosopher of science puts forward a theory of how science should proceed that would result, if put into practice, in a cessation of progress in science, that's a good sign there is something wrong with his theory. In fact, we might say it has been falsified. Now, to examine the case of Copernicus at greater length. The first thing that is important to note here is that Ptolemy's theory did not suffer from nearly the number of problems as did that of Copernicus as soon as it came out. For example, Copernicus "was puzzled by the variations he had observed in the brightness of the planet Mars. [But] Copernicus's own system was so far from answering to the phenomena in the case of Mars that Galileo in his main work on this subject praises him for clinging to his new theory though it contradicted observation..." (Butterfield, 1949, p. 23).

Copernicanism also violated many of the principles of the Aristotelian physics of his time. Copernicus could not explain why objects didn't fly off the rotating earth, why the earth didn't spin itself apart, or what kept celestial objects going in their orbits if not the motion transmitted from sphere to sphere in the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian view. As Butterfield writes:

"In fact, you had to throw over the very frameboard of existing science, and it was here that Copernicus clearly failed to provide an alternative. He provided a neater geometry of the heavens, but it was one which made nonsense of the reasons and explanations that had previously been given to account for the movements in the sky" (1949, p. 27).

Lots and lots of people will tell you that heliocentrism was disturbing when it was first being debated because it "displaced humanity from the center of the universe." But when I ask actual historians of science about this, they say there is just no evidence for this at all. Below is testimony to this effect: the center of the universe was its cesspit, and at the very center was hell and the demons: the very worst place to be of all! To get out of the center was a promotion:

It is a commonly held and widespread myth, that is unfortunately continually repeated in both popular and academic books, that one of the main reasons for the rejection of Copernicanism in the Early Modern period was the fact that it displaced the earth from its 'privileged' position at the centre of the then known universe. The truth is that the earth's position was regarded as anything but privileged and was more considered the garbage can of the universe as is nicely illustrated by this quote from Otto von Guericke from 1672:

CHAPTER 7

OBJECTIONS OF THE ASTRONOMERS AND NATURAL PHILOSOPHERS TO THE COPERNICAN SYSTEM

Since, however, almost everyone has been of the conviction that the earth is immobile since it is a heavy body, the dregs, as it were, of the universe and for this reason situated in the middle or the lowest region of the heaven...

Otto von Guericke; The New (So-Called) Magdeburg Experiments of Otto von Guericke, trans. with pref. by Margaret Glover Foley Ames. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht/Boston/London, 1994, pp 15 - 16. (my emphasis)

And here is a quote from Boethius, from The Consolation of Philosophy, written around 525 AD:

It is well known, and you have seen it demonstrated by astronomers, that beside the extent of the heavens, the circumference of the earth has the size of a point; that is to say, compared with the magnitude of the celestial sphere, it may be thought of as having no extent at all. The surface of the world, then, is small enough, and of it, as you have learnt from the geographer Ptolemy, approximately one quarter is inhabited by living beings known to us. If from this quarter you subtract in your mind all that is covered by sea and marshes and the vast area made desert by lack of moisture, then scarcely the smallest of regions is left for men to live in. This is the tiny point within a point, shut in and hedged about, in which you think of spreading your fame and extending your renown, as if a glory constricted within such tight and narrow confines could have any breadth or splendour. Remember, too, that this same narrow enclosure in which we live is the home of many nations which differ in language, customs and their whole way of life. Because of the difficulty of the journey, the difference of speech and the infrequence of trade, even the renown of great cities does not reach them, let alone the fame of individuals. Cicero mentions somewhere that in his time the fame of Rome had still not penetrated the Caucasus mountains, although the empire was then fully grown and an object of fear to the Parthians and other peoples in the east.'