Judging History

Wootton, David.

The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution,

New York: Harper, 2015.

Reprinted courtesy of The American Conservative.

Once, when I brought my young son in to see his pediatrician, the doctor asked me a number of questions, most of them quite reasonable. But then he asked, "Are there any guns in the house?"

Now as it happens, I have never owned a gun, and only have fired one once in my life, but I took umbrage at the question. As a doctor, this man was certainly more qualified than me to treat a gunshot wound. But his medical training gave him no special expertise in evaluating the trade-offs present in owning a gun, and I told him so.

A similarly unwarranted "expertise imperialism" occurs with historians. Historians are trained experts at examining historical evidence to determine what really happened in the past. (And no, the facts of history are not a "given" starting point, but a conclusion: physical evidence needs interpretation, kings have their scribes write down mendacious propaganda, and eye witnesses may be completely confused about what they saw.)

But historians, also being humans, often want to tell us how we should judge what happened in the past: Who were the greatest American presidents? Did Chamberlain act foolishly at Munich? Was Roosevelt justified in trying to pack the court? Of course, one must know the facts about such cases to render any sensible judgment about them, and historians who specialize in an area are certainly going to be aware of those facts. But so is any intelligent reader who reads a good book by such an historian.

In Michael Oakeshott's work On History, he explains that we can approach the past with various attitudes, and that those different attitudes create different pasts. For instance, we may contemplate the past in a state of artistic reverie, as Marcel Proust did in his masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time. This produces a poetic past, a past mined for its artistic yield. In it the "facts" are only important as material for the artist's imagination: to us as readers, it matters not whether Charles Swann ever existed, or whether, if he did, he really had a love affair with Odette de Crécy.

But more commonly we encounter what Oakeshott called the practical past: the past employed as a source of guidance to steer us through present perplexities. Once again, as with the poetical past, "the facts" are secondary, in this case, to the message. A paradigmatic example here is the story of George Washington chopping down a cherry tree, refusing to lie about his deed, and being praised by his father for his honesty. Whether or not Washington ever did such a thing is unimportant: the story works, regardless of its facticity, as advice against lying. But events that quite certainly occurred also can become part of the practical past when they are turned into lessons: Napoleon's hubris bringing him to his Waterloo, Paul Revere's daring saving the day, Joan of Arc's saintliness preserving French independence.

Oakeshott argues that the historical past is different from these other attitudes towards the past, in that its special focus is upon what the historical evidence indicates really occurred, and not the beauty of those events, or their lessons for us today. And it is that past that professional historians are uniquely qualified to comment upon.

All of these preliminaries are important to this review, because David Wootton here has written not a single book, but two intertwined ones. One of them, written by Wootton the highly skilled professional historian, seeks to overturn the recent consensus on the "Scientific Revolution," which has been that talk of a revolution is overblown, and what really happened was a gradual development of older ideas into what we now regard as modern science. In this work, Wootton mines his sources to great effect, arguing that, in fact, the Scientific Revolution really did represent a dramatic break with earlier approaches to understanding nature.

But mixed with that historical work is another in which David Wootton, advocate of science as the pinnacle of human knowledge, hopes to convince readers of his worldview. And the point of all of my preliminaries is to argue that there is no reason that Wootton's great achievement in his historical work should intimidate us into acquiescing to the conclusion of his philosophical work. And that is because that latter conclusion is not, and could not possibly be, the conclusion of an historical investigation, since it is not a conclusion about what really happened in the past. Instead, Wootton is forwarding a value judgment, about the relative worth of the different ways in which humans attempt to comprehend our world.

And Wootton knows that such attempts to cloak value judgments as historical conclusions has been subject to serious critique in the past, and so he takes time out from his central theses to forestall similar criticism here. He sets up a strawman version of Oakeshott's intellectual ally, Herbert Butterfield, and then knocks that scarecrow down. Wootton says of Butterfield:

"In 1931 he had published The Whig Interpretation of History... [In it] Butterfield argued... it was not the historian's job to praise those people in the past whose values and opinions they agreed with and criticize those with whom they disagreed; only God had the right to sit in judgment... It should be obvious that he was not right about this: no one, I trust, would want to read an account of slavery written by someone incapable of passing judgment."

But this is a caricature of what Butterfield wrote. Consider the following quotes from The Whig Interpretation of History:

"There can be no complaint against the historian who personally and privately has his preferences and antipathies..."

"If [the historian] deals in moral judgements at all he is trying to take upon himself a new dimension, and he is leaving that realm of historical explanation..."

So Butterfield quite explicitly says that, far from being "incapable of passing judgment," it is fine for historians to pass judgments as human beings. Butterfield personally is just as capable of disliking slavery as Wootton. Butterfield's point is that the historian's job is to determine what happened in the past, and condemning or praising various participants in that past is no part of that job. This is analogous to the principle that, as a physician, it is not the doctor's job to pass judgment on the sick who appear before him, but to cure them. Once Stalin or Gandhi is cured, the doctor is free to disparage the first and praise the latter. One may agree or disagree with this separation of roles, but it is far from the silliness that Wootton attributes to Butterfield.

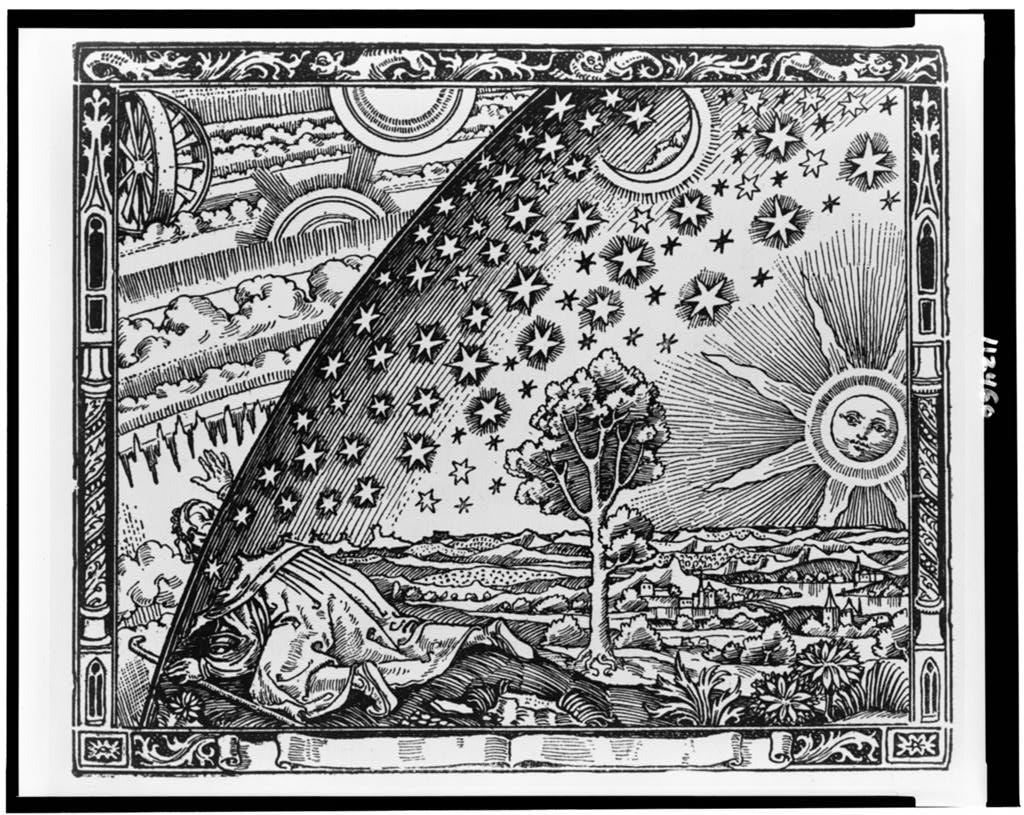

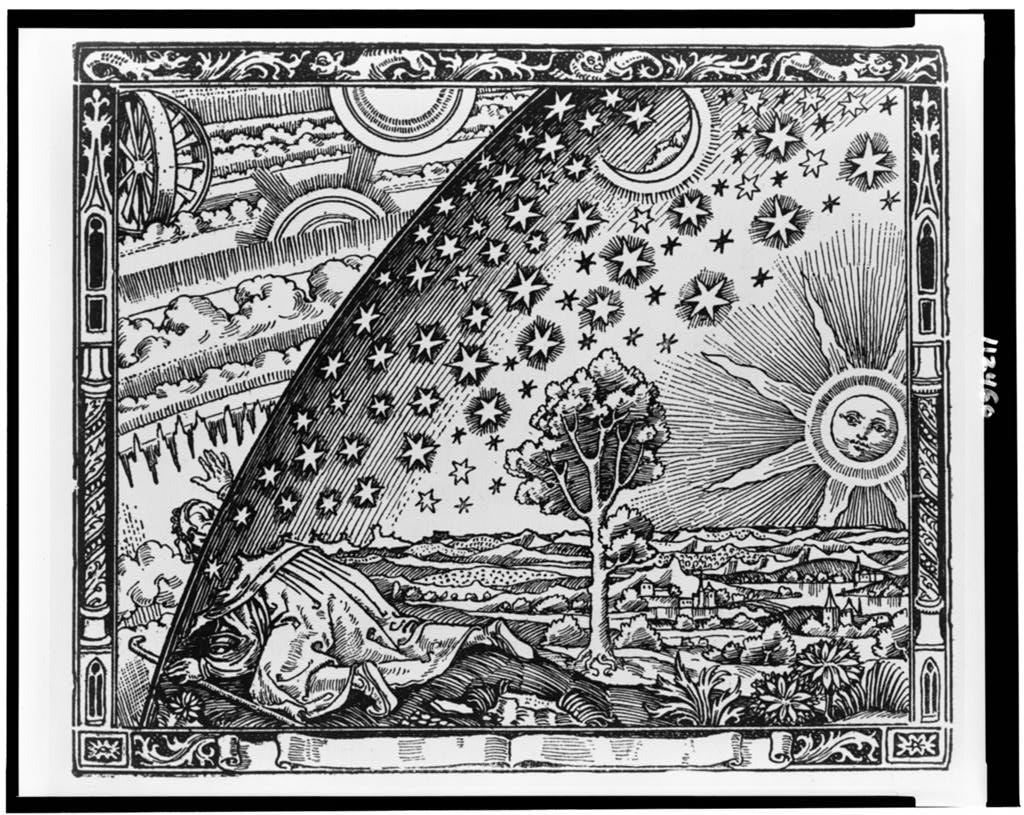

Returning to the main streams of the book, Wootton's great achievement in historical scholarship is a serious challenge to the "gradualist" thesis of scientific development, one I had myself had accepted as settled facct. (While I am not a professional historian of science, I formally studied the subject in graduate school, and have read avidly in it ever since.) Wootton presents extensive evidence, much of it linguistic, that something genuinely new was going on in the 16th and 17th centuries, something essentially different from the attempts of the ancient Greeks' or Medieval schoolmen's efforts at understanding the physical world. (An important caveat here: as a professional historian, Wootton certainly does not subscribe to the popular canard that the Middle Ages were a time of abysmal ignorance, during which no scientific advances occurred, just as his opponents would never deny that Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Harvey, Boyle, Pascal, Newton, etc. made significant advances over their Medieval predecessors. The professional debate is over how radical that advance was, not over whether it occurred or whether it built on earlier accomplishments.)

In particular, Wootton attempts to show that the concepts of facts, experiments, natural laws, scientific theories, and evidence all either altered radically or, indeed, came into being during the 16th and 17th centuries. For example, he claims, backed by extensive source material, that the very word "fact" only entered the English language in the middle of the 1600s. For anyone interested in the twists and turns of the debate on whether there really was a revolution in thought during those centuries, Wootton's work is must reading.

What's more, along the way we are treated to various, wonderful historical anecdotes; for instance, we discovered that what scientists consider simply out of the question has differed considerably over time, e.g.:

Eighteenth-century English and French scientists rejected the ample testimony as to the reality of meteorites, as we reject stories of alien abduction. On 13 September 1768 a large meteorite fell... [in] Pays de la Loire. Numerous people (all of them peasants) saw it fall. Three members of the Royal Academy of Sciences (including young Lavoisier) were sent to investigate. They concluded that lightning had struck a lump of sandstone on the ground; the idea of rocks falling from outer space was simply ridiculous.

I also learned something new about Descartes. I knew that his claim to have thought up everything in his philosophy from scratch was false: scholars have found many elements of it in his own schoolbooks. But I had thought he was simply deceiving himself. However, based on Wootton's description of how Descartes vehemently denied his considerable debt to Beeckman, it now seems to me more likely that he was consciously promoting what he knew to be a lie.

But now we must turn our attention to the more dubious of Wootton's two projects, that of asserting the superiority of science to all other forms of knowledge. Speaking of 'facts,' 'experiments,' 'hypotheses,' 'theories,' and 'laws of nature," he claims: "[These terms] served as a passage between Montaigne's world, a world of belief and misplaced conviction, and our world, the world of reliable and effective knowledge."

This is a remarkable contention: before science, human beings had no "reliable knowledge"! Our ancestors weren't sure whether planting seeds or stones would grow wheat. When they went to hunt deer, they didn't know if they should put arrowheads or fur on the end of their arrows. If they were thirsty, they were uncertain if they should ingest water or sand. When freezing, sometimes they put on furs, but other times they laid down naked in the snow: who knew which would work? (Wootton makes a passing nod to the reliability of practical knowledge before this quote, but he clearly regards it as nescience when compared to scientific knowledge.)

He does provide examples of extremely fanciful beliefs our forebears held, for example, that garlic negates the power of magnets. But, as Wootton himself notes, before the compass, magnets were rarely encountered and of no practical import. To place this in perspective, magnets were for people before 1400 as conservatives are to Park Slope progressives today: the people in the first term of the relationship have heard rumors that the entities in the second term exist, but they never have encountered and never expect to encounter them. And thus, as a modern Park Slope resident can believe the most outlandish things about conservatives with no practical consequence, so could a European of 1100 believe pretty much anything about magnets without it mattering much.

The misapprehension about knowledge plaguing Wootton becomes clear in this passage: "Evidence-Indices [e.g., smoke as a sign of fire] may always have been used in an unthinking way by people going about their daily business; but to elevate them into being a reliable basis for theoretical knowledge..."

Wootton claims the Scientific Revolution replaced a world of abysmal ignorance with one that for the first time contains true knowledge, because Wootton does not consider what ordinary people's day-to-day activities to entail thought at all. But this is wrong: To move from an index to what that index signifies is an act of interpretation. In other words, it is thinking. It may not be great thinking, it may not be theorizing, and the move may have become so habitual that the thinker barely notices the thought involved. But nevertheless, it is an act of intelligence, and constitutes a genuine form of knowledge, without which the human species would not have survived a week after it had evolved.

Given his embrace of scientism, it is unsurprising that Wootton deems the Scientific Revolution the most important event in human history since the Neolithic Revolution. So it is, per Wootton, more important than, for instance, the Axial Age, the discovery of monotheism, the creation of philosophy, or the rise of Christianity. But what historical evidence lies behind such a claim? Wootton might argue that the Scientific Revolution transformed humans' material life more than any of those other happenings, but why should "material transformation" be the decisive measure of "importance"? After all, "importance" is itself not a material thing that can be measured. And so, when I claim that Wootton has produced both a great work of historical scholarship, and a slipshod piece of philosophical argumentation, I wonder how his materialist bias would measure my claim?